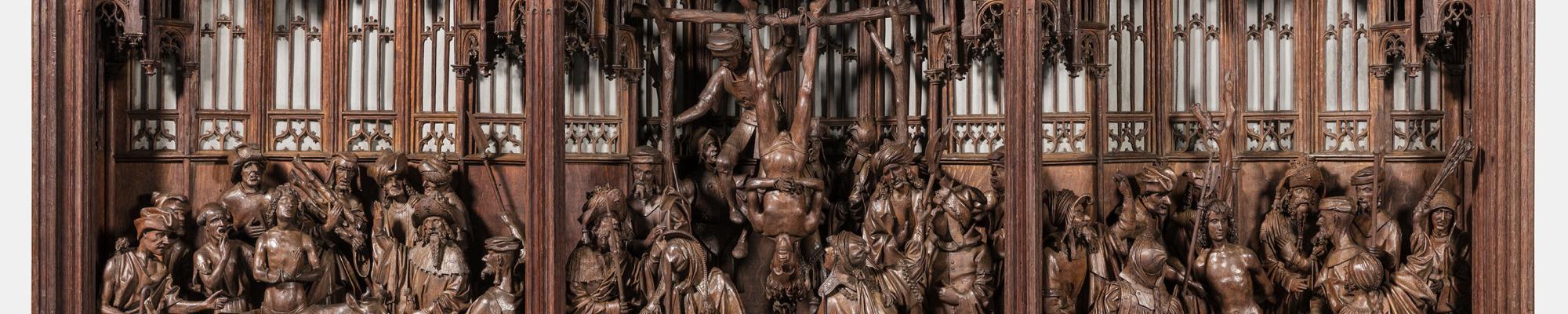

Altarpiece of Saint Georges

The altarpiece of Saint George: a spectacular restoration

Since April 2021 and after three years of research and restoration, Jan II Borman's Saint George Altarpiece (1493) is back on display in the Gothic-Renaissance-Baroque section of the Art & History Museum. The interdisciplinary study, carried out in collaboration with the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, has made unexpected discoveries and shed light on age-old mysteries. After almost two centuries, the beautifully carved statuettes have been returned to their original place in the monumental masterpiece, which has been restored. This project was made possible with the support of the King Baudouin Foundation (René and Karin Jonckheere Fund).

3D cinema before its time

The Altarpiece of St. George is one of the most spectacular wooden sculptures in Western history: an impressive ensemble measuring no less than 5 metres wide and 1.60 metres high, with over 80 meticulously detailed figures. It is the masterpiece of Jan II Borman, the undisputed master of the eponymous dynasty of Brussels artists, described in his lifetime as the best sculptor of his time. The master signed and dated this work as 1493.

The late Gothic scenes are undoubtedly timeless and of exceptional quality. They captivate the viewer with their cinematic compositions, expressiveness, and the virtuosity of the carvings. The figures are depicted during the action as if in a freeze frame. In a series of seven scenes, Borman brings the atrocious martyrdom of St George to life. The fearless hero is suspended by his feet over the flames, eviscerated, and decapitated.

Interdisciplinary research

The exhibition Borman and Sons - The Best Sculptors in the M Museum in Leuven was an ideal opportunity for Emile van Binnebeke, curator of European sculpture at the MRAH, to examine in detail the masterpieces of the Borman dynasty. He collaborated with Emmanuelle Mercier, an expert in woodcarving at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, and her lab colleagues. The research was conducted in parallel with the restoration of the altarpiece.

The only work signed by Jan II Borman, of which a copy of the commissioning document has been preserved, the St George altarpiece is the key to understanding his creative genius. The altarpiece has always been shrouded in mystery. Was it originally polychromed like the other Flemish altarpieces? In what context was it created? And how can we explain the seemingly incoherent order of the scenes, which do not correspond to the legend and surprisingly begin with the saint's death?

Hidden secrets

To examine the altarpiece from all angles and to clean it thoroughly, the 48 wooden elements were carefully dismantled. Alongside various fragments of wood that had fallen apart over the years, such as fingers, earrings and architectural details, Emmanuelle Mercier and her team discovered a small carved figure of a prayer hidden beneath the scenes. Radiocarbon analysis reveals that the wood dates from the time of the altarpiece. Borman may have hidden this ex-voto as a form of prayer or gratitude. When the restorers of the Institute dismantled the central scene, they also found a piece of parchment from their predecessor, a person named Sohest, which mentions that he restored the altarpiece in 1835!

The unpredictable order of the scenes was eventually explained by studying the locations of the original pegs and nails used to fix the settings in the box. It is clear from these that Sohest dismantled and replaced the scenes in a different order for unknown reasons. In the course of the current restoration, the storyline established by Jan II Borman has finally been reconstructed.

A look at the 19th century

When curator Emile van Binnebeke (MRAH) became aware of the Sohest scroll, all the puzzle pieces started to form. On another altarpiece in our collection, the Wannabecq altarpiece (1530), I noticed the same blue-grey paint on the back of the windows. I could relate this to a document from 1843 in which a certain Sohest requests payment for his restoration work on the Wannabecq altarpiece; the same restorer.

The discovery of the parchment, dated 1835, is also a surprise, as it was thought that the altarpiece of St. George had only officially entered the Art & History Museum in 1848. During the dismantling, the signature of Sohest and the date 1832 were also found on four reworked angel statues. Van Binnebeke says: Not only does this give us an idea of the duration of his intervention, but we also learn that investments were made in the restoration of the altarpiece as early as the early 1830s, just after the fight for Belgium's independence.This casts a new light on the nascent ambition to create a national museum.

Borman's spectacular technique

Emmanuelle Mercier, woodcarving expert: Careful observation, together with laboratory analysis, revealed that, contrary to custom, the altarpiece was never covered with polychromy. This may explain the extraordinary woodwork, especially in the meticulous details of the rich costumes, which would be lost even under the thinnest layer of paint. Jan II Borman also amazed us with his ability to create complex compositions with several figures from a single block of wood without any stitching. Dendrochronological analyses have shown that the sculptor used a regional oak that was rather tough to work—proof of his exceptional talent.

The restorers removed the dust and dirt from the multitude of reliefs. They reattached the pieces of wood that had fallen into the box over the years and consolidated the areas weakened by woodworm. They also homogenised and lightened the various coloured patinas applied since the 19th century, including a wax that had blackened all faces. The physical qualities of the sculpture's relief and the meticulous details are thus better highlighted.

Political intrigues

The archival and art-historical research, in its turn, provides an understanding of the St. George retable. Curator Emile van Binnebeke interprets the commissioning of the altarpiece, by the Leuven Great Crossbowmen's Guild for their Chapel of the Virgin Mary, as a political game at the highest level. To gain the favour of Maximilian of Austria, conqueror of the revolt of the Brabant and Flemish cities, they deliberately asked Jan II Borman to carry out the assignment, as he was a member of the Brussels Chambers of rhetoric 'De Lelie' (The Lily) under the patronage of Maximilian. St. George was the personal patron saint of the archduke, who used the martyrdom of the holy man for political ends.

Van Binnebeke: The Great Guild may have succeeded in its gamble: although it did not side with Maximilian during the revolt, it suffered no consequences. This may have been a bittersweet victory. Indeed, the city of Leuven went bankrupt because of the revolt. The treasury of the Great Guild was almost empty. So after Borman's payment, there would not have been enough money to colour the altarpiece.

This research project was carried out with the support of the King Baudouin Foundation, more specifically the René and Karin Jonckheere Fund, whose objective is to safeguard movable cultural heritage. This Fund supports the conservation or restoration of works of art that bear witness to the international dimension of Brussels, works that are kept in Brussels museums. However, the Fund may also intervene in favour of works kept in museums and libraries elsewhere in Europe.

The Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage is a federal non-profit institution that takes care of Belgium's heritage: art, monuments and items of historical value.

Marks-on-Art database

The RMAH are one of the partners of the Marks-on-Art database project supported by the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History) in The Hague. Since early November of 2024, the database can be accessed through this link.

Thanks to the Marks-on-Art project, it is now possible to see and research all kinds of marks but also workbench marks and signatures on works of art. The RMAH have been a partner since day one in the project, which also allowed a large number of medieval sculptures and altarpieces to be examined. At the moment, not all objects and marks that were researched in the Museum's collection are accessible in the database. Through the years, the research team has carried out this research all over Europe and generated a mass of data, all of which must be processed before being published in the database. In the coming years, objects from the Museum's collection will be added frequently. Quite a few marks on, for example, fragments of retables from Bassine are already on display at the Royal Library of Belgium and in the permanent collections of the RMAH, such as the "Mechelen Dolls" of Saint Barbara (inv. 6570) or Saint Peter (inv. 2886).

The wooden carved and polychromed retables were also examined. Especially on the pieces of Antwerp, numerous so-called Antwerp hands, a mark of quality, were found. On some of them, there are about several dozen marks, all of which were measured individually and photographed and described with different types of light. Besides these little hands, a hallmark of the city of Antwerp, consisting of an image of the Antwerp castle with a pair of hands above it, can also be found on two retables.

Those who start browsing the database come across all sorts of surprising things that usually remain hidden from museum or church visitors, such as the marks found on the backs of works of art. For now, some of the backs of retables from Leuven (Antwerps Passie Retabel, from a. 1520-1525) and Herentals (retable of HH. Crispinus and Crispianus by Pasquier Borman from ca. 1520) are included in the database. On it, you can see, for example, joiner's marks from Brussels (compass and scraper) or a woodmark which is a kind of property mark referring to the hand trade.

To research the marks, all objects that were considered were extensively re-photographed and measured. For more information about the collection of medieval sculpture, you can visit Carmentis, the Museum's online collection database.